In order to describe the earliest plants, one has to say something about plant structure generally.

In order to describe the earliest plants, one has to say something about plant structure generally.

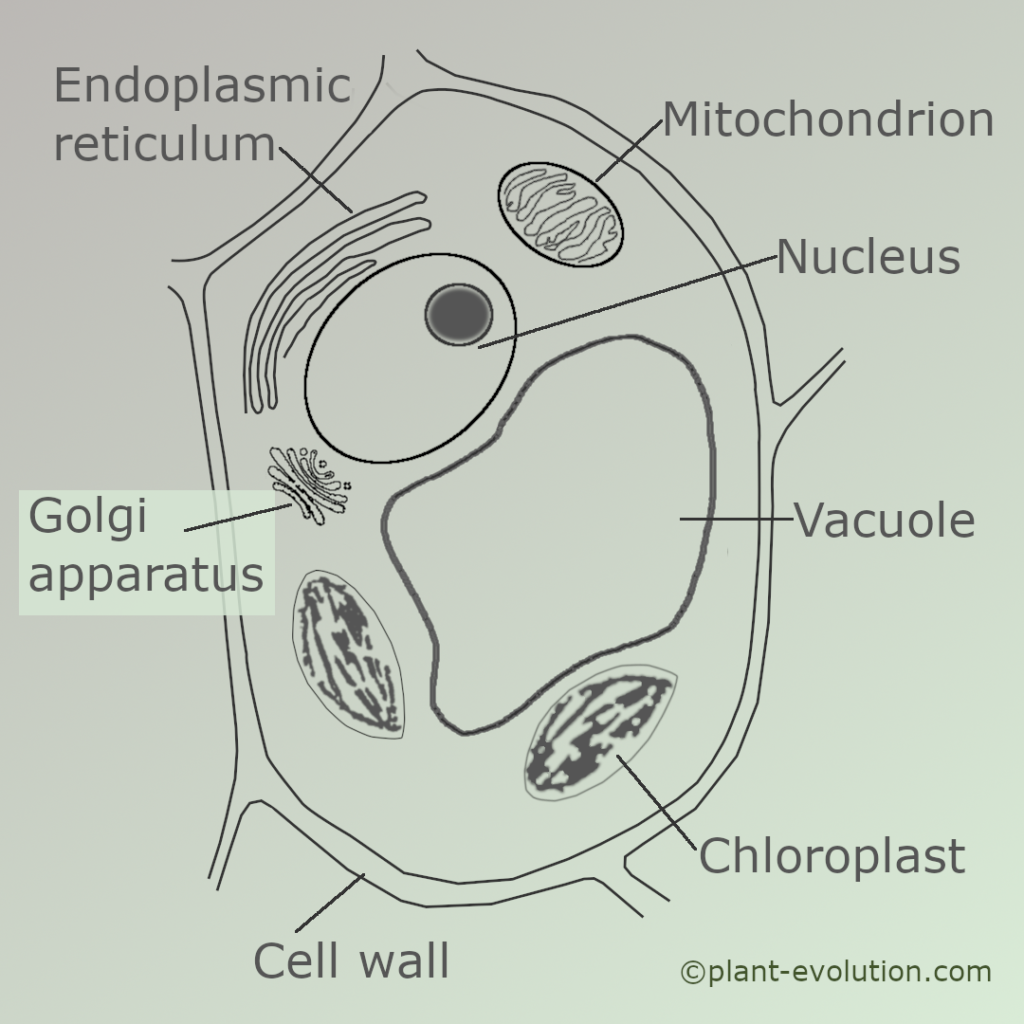

Most plants are composed of huge numbers of small, box-like bodies called cells which are usually so small that they can only be distinguished with the aid of a microscope, their dimensions being measured in small fractions of a millimetre.

Some plants consist of one cell only; these are the bacteria and single-celled algae. It appears that the ancestral line of plants descended from such single-celled plants.

Some unicellular plants, the algae, are the cause of the ‘greening’ of aquaria and ponds, particularly in warm weather.

A typical algal cell is enclosed by a cellulose wall and contains one or more green structures called chloroplasts which can absorb the energy of sunlight. The latter is used in the process called photosynthesis to build up food materials such as carbohydrates (mostly starch and sugars), lipids (fats and oils) and proteins.

It is this capacity to produce food that makes plants so vitally important to life on Earth.

All animals ultimately depend on plants for food. If all plants died out, then animals would as well. It was the fact that the sun’s energy could be trapped by plants that enabled life to flourish on Earth.

Also, another particularly important consequence of the activity of the early plants was their release of oxygen as a waste product of photosynthesis. The build-up of this gas in Earth’s atmosphere during the early period of plant evolution enabled animal life to develop as well. The plants provided not only food for animals but also a suitable atmosphere for them to breathe.

As distinct from animals, plants are truly self-supporting. As long as they have light energy, some carbon dioxide in the air (as little as 0.03% will do), water and minerals, they can grow perfectly well. The existence of all these requirements in the early history of the Earth provided the set of essential conditions for plant life.

The progression from unicellular to multicellular organisms

The progression from a state where a plant consists of only one cell to a situation where it comprises a conglomeration of cells confers considerable advantages.

These lie in the division of labour that becomes possible amongst the many cells. Various types may specialize in a number of ways so that, for example, some may exclusively produce food material while others provide for the reproduction of the species. The first type of cells could be so modified that they can produce the maximum amount of food whereas the second type may produce no food at all but be supported by the food-producers.